I’m about to take of for a trip to Israel for work which, coming immediately after a visit by my parents has conspired to slow my progress. Today, I took a deep breath and started looking into moisture sensors in a serious way.

Currently, I have two probes running – the Vegetronix V400 and a resistive sensor of two galvanized nails shoved into the soil. While i’m collecting data and waiting to compare the output, my goal is to have a bunch of sensors placed around my garden and i’d like them to be homogeneous so I don’t have to worry about multiple sensor peculiarities. Time to dig into moisture sensing techniques and start evaluating options to scale my little sensing operation up.

Resistance Sensors

Most home build hobby sensors use the conductive properties of water to check for resistance changes. There are two basic types – those that probe the soil directly, essentially shoving two stakes in the ground, and those that use a different medium to check for moisture.

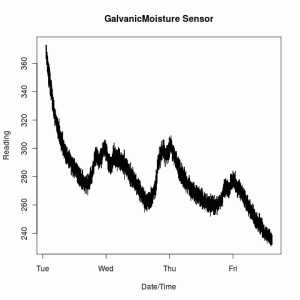

The simplest option, of which I have one in the ground right now, is to test the resistivity of the soil directly by shoving two probes in the soil and measuring the resistance across them. Using two galvanized nails makes this incredibly cheap which is why they are quite so common among hobbyists. With the low cost comes a number of downsides. There is a high temperature dependency, so to be accurate in an outdoor environment requires adding a soil temperature probe. The chart to the right is the resistance across two approximately three inch galvanized nails spaced about an inch apart and you can clearly see a diurnal periodicity as the temperature changes. These sensors also suffer from soil composition and salinity dependencies – add fertilizer and your readings could be quite different. As they’re typically read using DC current, the probes do have a limited life span as electrolysis occurs. Typically, this effect is controlled for by only passing current through the probes at the time the reading is taken and simply replacing the probes yearly.

The simplest option, of which I have one in the ground right now, is to test the resistivity of the soil directly by shoving two probes in the soil and measuring the resistance across them. Using two galvanized nails makes this incredibly cheap which is why they are quite so common among hobbyists. With the low cost comes a number of downsides. There is a high temperature dependency, so to be accurate in an outdoor environment requires adding a soil temperature probe. The chart to the right is the resistance across two approximately three inch galvanized nails spaced about an inch apart and you can clearly see a diurnal periodicity as the temperature changes. These sensors also suffer from soil composition and salinity dependencies – add fertilizer and your readings could be quite different. As they’re typically read using DC current, the probes do have a limited life span as electrolysis occurs. Typically, this effect is controlled for by only passing current through the probes at the time the reading is taken and simply replacing the probes yearly.

Cheap Vegetable Garderner is something of the granddaddy it seems of the type using a separate medium, in this case Plaster of Paris. Conceptually, the plaster absorbs water and dries out in concert with the soil it is buried in. Two conductive probes are embedded in the plaster and the resistivity between them is measured. While in principle, this controls for the soil composition, it adds its own problems. As explained over at GardenBot,

Initially when the plaster is dry, it has very high resistance (as you would expect). The problem is that plaster has an affinity for moisture, so as soon as the plaster comes in contact with any moisture at all, the sensor reading will drop to a very low resistance. And even if you completely saturate the sensor, you will not get the resistance to drop much lower than that.

With the problems in these types of sensors, essentially everywhere they’re used people just wave their hands and point out that for the application and given the cost they’re adequate. My project isn’t about being simply adequate, it is about learning and overkill otherwise I would have set up a simple timer and called it a day. So with that in mind, on we go to sensing capacitance!

Capacitance Sensors

Resistance isn’t the only electrical property to change with the addition of water into soil. The dielectric permittivity changes as well and can be probed in a number of ways, referred to in the literature as frequency domain sensing. Essentially, the dielectric of water is significantly higher than any of the other materials in the system causing the capacitance reading to be dominated by the water content.

Making this work requires a bit more circuitry than a simple resistance sensor which is why I think they aren’t commonly used in the DIY community. Mostly hints pop up in the occasional comment on one of the other methods. I believe this is actually the method employed by the Vegetronix v400, though they won’t say exactly the technique employed.

Fortunately, there is one well documented project that uses this technique. I’m not sure how exactly I found the link, but off of this page there is this paper titled “WiGreen Soil Moisture Monitoring System.” The project itself is pretty cool using mesh networking to have a sensor network reading soil moisture. Down on page 35, they go into detail of how they read the capacitance and then on page 48 are their circuit diagrams and PCB layout.

Fortunately, there is one well documented project that uses this technique. I’m not sure how exactly I found the link, but off of this page there is this paper titled “WiGreen Soil Moisture Monitoring System.” The project itself is pretty cool using mesh networking to have a sensor network reading soil moisture. Down on page 35, they go into detail of how they read the capacitance and then on page 48 are their circuit diagrams and PCB layout.

At this point, I’ve decided to try to construct my own capacitance sensor and have some design experimentation to be done. My current plan is to build the 555 circuit independent of the probe component so I can test different soil probe options – i.e. the coated spires mentioned in the comment or embed them in the pcb as in the WiGreen project. Expect more on this as I start experimenting.

I’m also not completely writing off a resistive approach. I’ll be putting a soil temperature sensor into the system soon and will use it to try to control for the temperature variation observed.